"In this and like communities,” Abraham Lincoln observed, “public sentiment is everything. With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it, nothing can succeed. Consequently he who moulds public sentiment, goes deeper than he who enacts statutes or pronounces opinions.” The formation of public sentiment, Lincoln believed, is not the whole of statesmanship, but it is the deepest and most important of the statesman’s tasks.

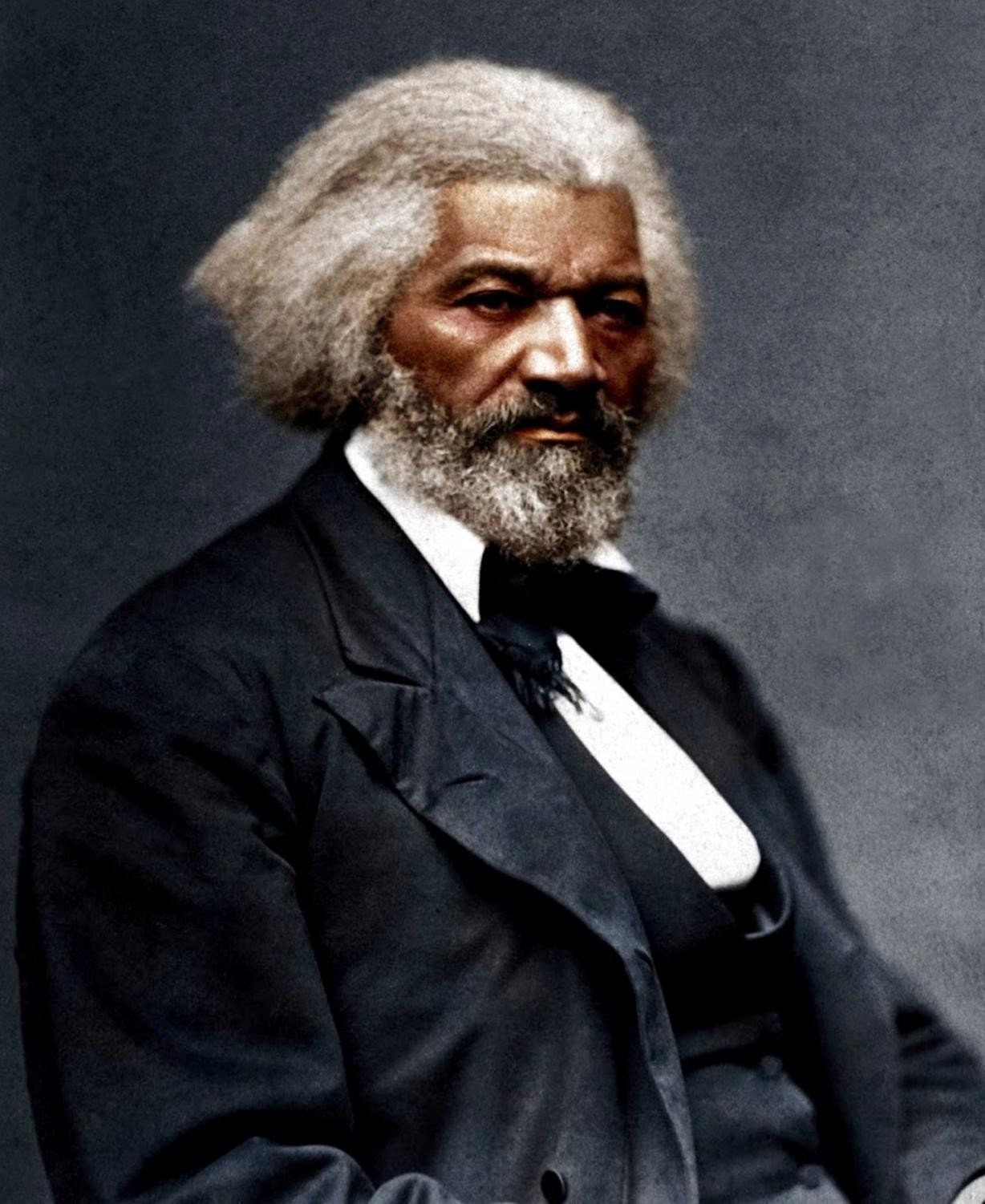

Frederick Douglass enacted no statutes and pronounced no authoritative judicial opinions; he commanded no armies and wrote no constitutions; he founded no political institutions or orders. He was not a statesman in the restrictive usage of the term, confined to the class of public officials. He was instead, in 19th-century parlance, only an agitator—an activist who occupied himself mainly in “the foolishness of preaching,” as he liked to call it, urging public officials and other fellow citizens to action in the service of the great moral causes of the day. Yet he was no ordinary agitator. He was the “Great Agitator” of 19th century America, the indispensable counterpart to the Great Emancipator. In a career spanning over 50 years, Douglass labored in his way, as Abraham Lincoln did in his, to renew and reinvigorate, and also to broaden and deepen, his country’s dedication to its first principles. Today he is remembered, with virtually universal admiration, as a preeminent teacher and exemplar of America’s moral meaning and mission.

#AmericanGreatness #FrederickDouglass #Statesmanship #History